All the Light We Cannot See by Anthony Doerr

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

All the Light We Cannot See by Anthony Doerr

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

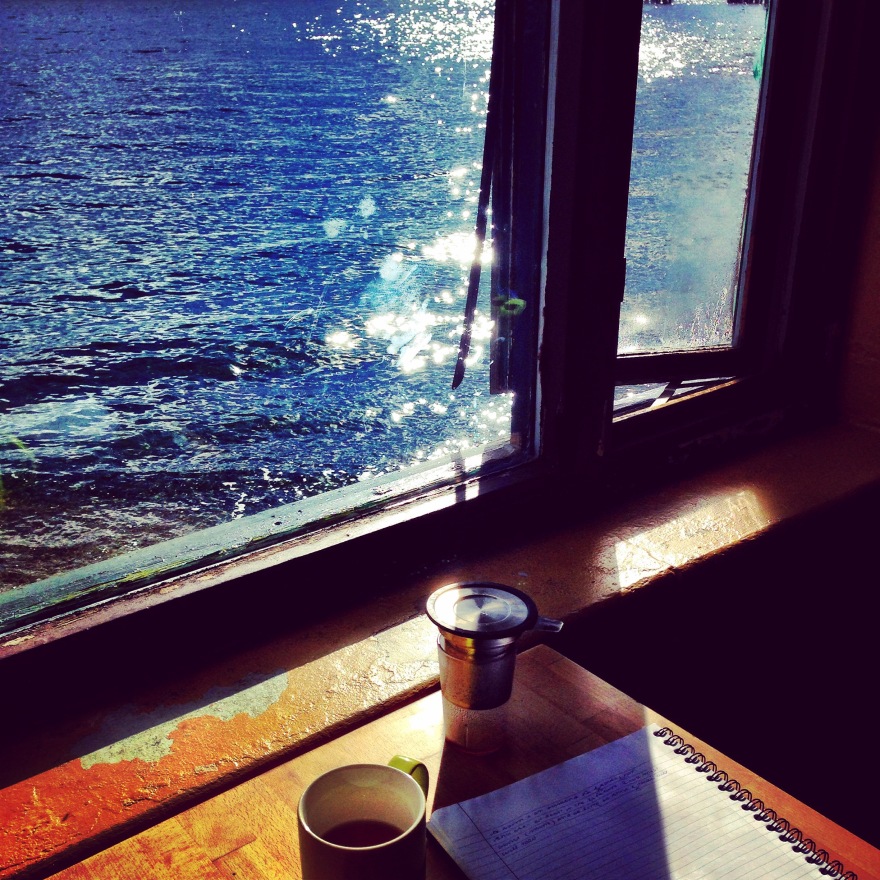

When I travel, I gravitate to the small, forgotten places—the crumbling ruins rather than the soaring cathedrals; villages with their backs turned to the road instead of bustling capital cities. I wonder at the secrets that lie within the stillness, the stories that whisper in the broken stone or behind shuttered windows.

I’d not read Anthony Doerr before All The Light We Cannot See, but as I lost myself in the delicate suite tendresse of this novel, I felt I’d found a kindred spirit. From the grandeur of European cities and the drama of war, he uncovers the gems hidden in quiet, forgotten lives.

The trope of two star-crossed young protagonists—(a blind French girl, an orphaned German boy) and the hints of fable woven through the characters’ childhoods, set against the dramatic backdrop of opposing countries on the brink of a war—would seem to tread familiar ground.

But nothing in this shimmering tapestry of a novel is like anything I’ve read before.

The story opens in Saint-Malo on France’s Breton coast—an ancient walled city where the high tides swamp medieval cellars. In August 1944, the town is occupied by German forces and shattered by Allied bombing. Alone in her home, sixteen-year-old Marie-Laure LeBlanc catches one of the hundreds of leaflets falling from the sky. It smells of new ink, but no one is around to tell her what it says.

Just a few streets away, Werner Pfenning, a young German soldier, is slowly suffocating in the foundation of a bombed hotel, trying to raise a signal on his radio. Finding voices in the still and empty dark has been his gift since he was a child, trapped in an orphanage in a German coal mining town. At last, he hears the voice of a girl—Marie-Laure—reading passages from Jules Verne’s Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea.

How these two lives come together is the simple, melodic premise of this symphonic novel. Layered into the composition are wonders of science, literature, and music, the horrors of war, poverty, and occupation, and the legend of a priceless blue diamond known as the Sea of Flames.

The light in the novel’s title takes many metaphorical forms. It is the light Marie-Laure’s father, the locksmith at the Museum of Natural History in Paris, shines on the world for his blind daughter. He creates intricate models of their Paris and Saint-Malo neighborhoods so that Marie-Laure can memorize her world with her fingers and not fear what her eyes cannot see. It is the light her father offers in the lies he writes after he is taken prisoner. It is the light of the people left behind who love and care for a brave, perceptive child. It is the light of the Resistance, a flame of hope and defiance.

The light in Werner’s life is much dimmer. His scientific genius is recognized and he is taken from the orphanage—saved from certain death in the coal mines—and sent to a Hitler Youth academy, where hope is extinguished by duty. He becomes a radio operator in service of the Führer, and certain death awaits him in Leningrad or Poland or Berlin. Science, math, and distant voices transmitting in the dark are his only lights.

The blue flame pulsing from a priceless diamond with a cruel past is another kind of light—one followed by sinister characters who use the trappings of power during the chaos of war to pursue their obsessions to the most bitter ends.

Anthony Doerr’s prose is lovely. It pirouettes on the fine line between lush and lyrical, flirting with magical realism, but never leaving solid ground. The imagination it takes to bring a reader into the head of a blind child learning to navigate her world so that we see, feel, smell, and hear as she does is breathtaking. The ability to evoke empathy without tumbling into sentimentality is admirable. The weaving together of so many scientific and historical details so that the reader is spellbound instead of belabored is nothing short of brilliant.

Structurally, All The Light We Cannot See is bold, its suspense masterful, its prose confident and beautiful. But it is the fragility and strength of Anthony Doerr’s characters that linger longest after the novel’s final pages. Highly recommended; one of this year’s best.