I travelled to France last month with a story in my heart. It's a story I've carried around for years—one I chronicled here: The Prisoner's Hands—and I spent time gathering details of place and researching the region's history during WWII. I thought, having seen through the writing of two novels, I was ready to undertake something nearly bigger than me. This story reaches far beyond the realm of alternative history I created in Refuge of Doves. There, my goal was to invoke a sense of place and time, but not to mire the narrative in medieval depths or lose a sense of playful speculation.

But I'm wasn't looking to retouch history here. Not with this story.

A book reviewer commented recently that the WWII literary idiom has been done ad nauseam. In the words of Love and Rockets, It's all the same thing; No new tale to tell. The world doesn't need any more stories from WWII.

As a reader fascinated by literature and research emanating from and inspired by WWI through the end of the Second World War, I couldn't disagree more. There will always be room and readers for stories from these eras, as long as the stories are well told.

In the past week I've read two extraordinary novels that take place during WWII: Anthony Doerr's All The Light We Cannot See, set in France and Germany; and Richard Flanagan's The Narrow Road to the Deep North, set in southeast Asia and Australia. Doerr's novel was just nominated for the National Book Award; Flanagan's won the 2014 Man Booker Prize. Both are beloved by professional critics and every day readers like myself. So yes, there is room for more WWII stories.

But one night, deep in jet lag insomnia, as I read All The Light We Cannot See, I realized I had to set aside my story. I came to accept that I am not yet the writer I need to be to tell a story deeply layered with sociopolitical nuance. Nor am I yet the researcher who could create the authenticity readers would rightly expect.

Tony Doerr spent ten years researching, crafting, and writing All The Light We Cannot See. Richard Flanagan wrote a novel steeped in so much historical detail and personal history (his father survived the Burma Death Railway—the subject of The Narrow Road to the Deep North), I can only guess he spent years carefully choosing each detail.

The understanding came laden with sadness and relief and not a small measure of anxiety for this writer. Setting aside a story I'd been thinking about for so long, that I spent time in France researching, meant I'd opened a yawning chasm of "Now what do I do?" My post-holiday plan, when I knew I would need to work on something new as I began the agent query process for Refuge of Doves and sought beta readers for Crows of Beara, had been to dive straight into a new novel.

Suddenly, I was without a story. I had no plan.

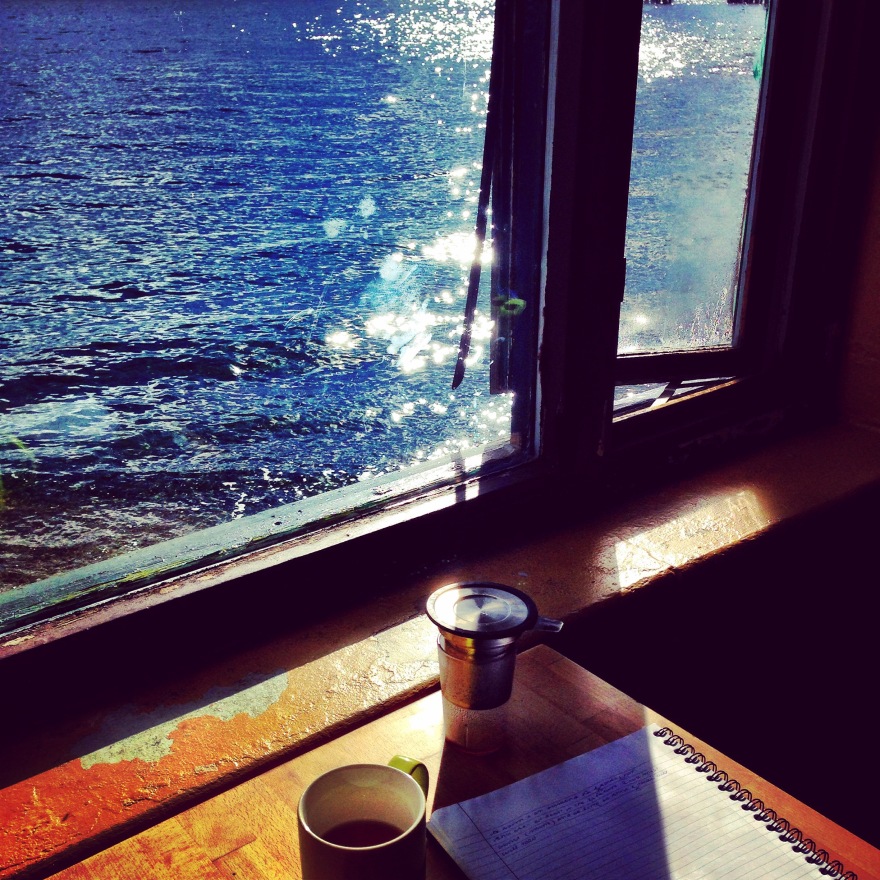

But if I've learned anything along this writer's journey, it's to trust that the next story is always there, shimmering at the edges of my peripheral vision, just within earshot. If I let go of trying to capture it and wait quietly, it will settle on my shoulder like a rare and fragile butterfly, or beam out like a piercing ray of sun from a rent in a storm cloud.

And come it did, during the middle of a writing workshop the week after our return. The story idea isn't new—in fact, its themes and some its characters have appeared in at least one of my short stories—but the Eureka moment came only after I'd let go of the search. Suddenly, quite suddenly, at 2:45 on a rainy Saturday afternoon in late October, I had my premise, my protagonist, and the quivering butterfly of a plot.

Let the writing begin.