Brown Girl Dreaming by Jacqueline Woodson

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

Brown Girl Dreaming by Jacqueline Woodson

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

My only reading goal for 2015 is to read more poetry. Without design—just luck of the queue at the library—brown girl dreaming, a memoir in verse, was the first book that landed in my hands this year. There is something sublime in that serendipity. Each and every page of brown girl dreaming is a gift of wisdom and innocence and discovery. Heartbreak. Joy. Family. Loneliness. Childhood. History. I savored and smiled as I read. I wept. After I read it, I rushed out to buy a copy for myself. I wish I could buy copies for the world.

The book’s opening poem signals the story Jacqueline Woodson seeks to tell:

I am born on a Tuesday at University Hospital Columbus, Ohio, USA— A country caught

Between Black and White.

Woodson reminds us that when she was born in 1963, “...only seven years had passed since Rose Parks refused to give up her seat on a city bus” in Montgomery, Alabama. The author, too, is of the South, but also of the Midwest and of the North. She moved with her mother, sister, and brother to Greenville, South Carolina—to her mother’s family—when she was a toddler, and then to Brooklyn, New York in elementary school.

brown girl dreaming is also the story of a little girl finding her voice. In Woodson’s case, it was the discovery that words and stories belonged to her—she just needed the time to meet them on her own terms:

I am not my sister. Words from the books curl around each other make little sense until I read them again and again, the story settling into memory. Too slow my teacher says. Read Faster. Too babyish, the teacher says. Read older. But I don't want to read faster or older or any way else that might make the story disappear too quickly from where it's settling inside my brain, slowly becoming a part of me. A story I will remember long after I've read it for the second, third, tenth, hundredth time.

There is such joy and love in her verse, a profound appreciation for her family and for the places that make up her visions of home. She writes of her mother’s parents in South Carolina:

So the first time my mother goes to New York City we don’t know to be sad, the weight of our grandparents’ love like a blanket with us beneath it, safe and warm.

And of Brooklyn:

We take our food out to her stoop just as the grown-ups start dancing merengue, the women lifting their long dresses to show off their fast-moving feet, the men clapping and yelling, Baila! Baila! until the living room floor disappears.

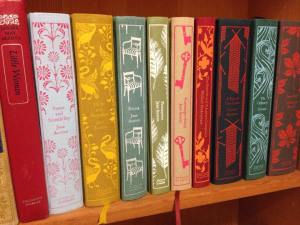

You may find brown girl dreaming on the fiction shelves of bookstores and libraries, for it is classified as a “fictionalized memoir.” Leaving aside debates of genre, it is far more likely to find a readership from these fiction shelves, and that is a good and necessary thing. Memoir and free verse may seem like odd companions, particularly in a book meant for younger readers, but oh, what a stellar opportunity to read and teach the power of poetry.

brown girl dreaming received the 2014 National Book Award for Young People’s Literature and is ostensibly a book meant for middle-grade readers, but it is timeless in its grace and eloquence. I recommend it to everyone, regardless of age.

Were I a pre-teen, I know I’d be reading this at every available moment: at the breakfast table, on the bus, in the cafeteria, in my room instead of suffering through long division homework and answering questions on the Emancipation Proclamation at the end of chapter 27 in my Social Studies text. The intimacy and immediacy of brown girl dreaming feels like a secret passed between BFFs, a Technicolor “now” of an After-School Special, the story of an American kid my age that is at once familiar in emotion and exotic in setting.

Were I the parent of a pre-teen or a younger child, we would read this together, for this is the history of America in the 1960s, and it offers so many of those “teachable moments”: opportunities to reach for history books, to seek out primary sources, to watch videos of speeches and documentaries of a time that is both distant, yet still very much at hand. The same would hold true for a book club of adults. brown girl dreaming can serve as a touchstone for African-American literature and history, which is our shared history.

As an adult, I read this with humility and wonder, enchanted by the voice of young Jacqueline Woodson as she discovers the importance of place, self, family, and words. As a writer, I am awed and overjoyed by the beauty of her language, by the richness of her verse.

Even the silence has a story to tell you. Just listen. Listen.

The building collapsed in a heap of stone and brick and beams and dust in the February 2011 earthquake. These are my dressiest shoes and I reckon they’ll be around a while. But I don’t have a thing to wear with them.

The building collapsed in a heap of stone and brick and beams and dust in the February 2011 earthquake. These are my dressiest shoes and I reckon they’ll be around a while. But I don’t have a thing to wear with them.