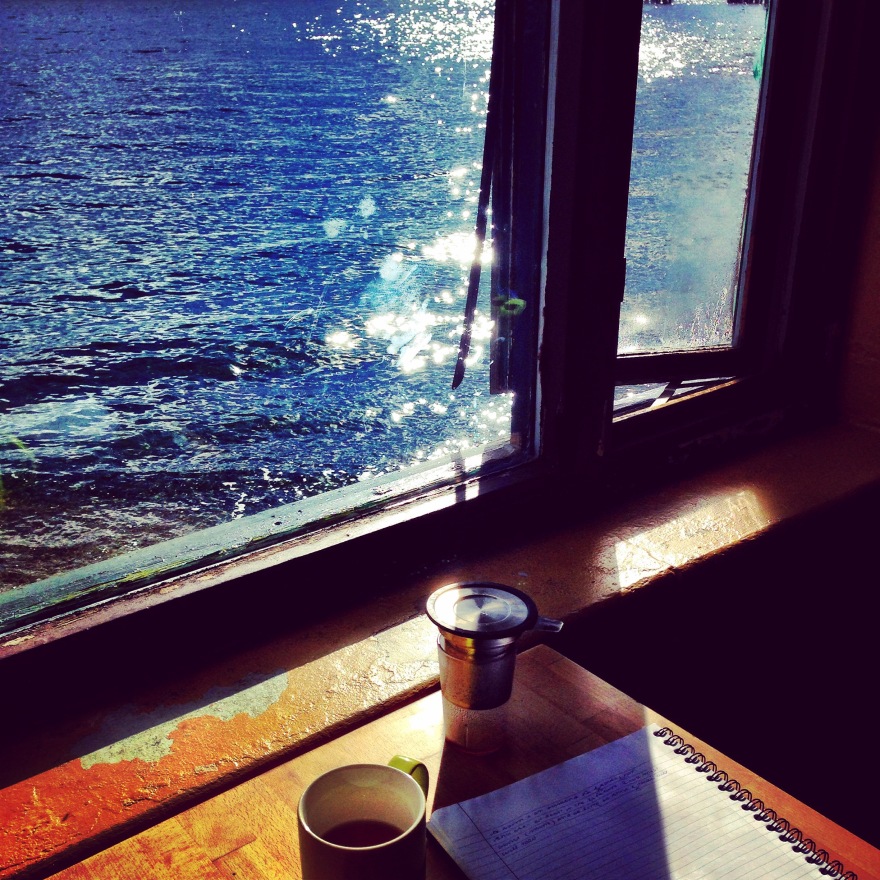

I wondered as the year began—my first as a full-time writer—if I would have much time to read, if I could afford the time away from writing. One hundred and thirteen books later, I no longer wonder. The more I write, the more reading has become essential to my writing, as I chronicled earlier this year: If You Don't Have Time to Read.

This has been the most astonishing and revelatory year of reading for this writer, ever. A year which saw me read my first Virginia Woolf and Sherman Alexie and Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie; discover Francesca Marciano, Rene Denfeld, and Leanne O'Sullivan; and be rewarded again by Tim Winton, Colm Tóibín, Niall Williams, and Margaret Atwood. So many books touched me, tore me open, provided delight, and a very few that just didn't connect. It happens.

Some stats: Female/Male Authors: 57/56; Memoir: 11; Poetry: 4 (oh, my reading goal for 2015 is to triple this!); Writing Craft: 6; Religion/Philosophy: 7; Young Adult: 5; Food/Wine: 1; Mystery/Suspense: 7; History/Reference: 6; Essays: 3. The rest, sixty-three if I did my math correctly, would be literary fiction, including seven short story collections.

I've pasted excerpts from my Goodreads reviews in the list below.

NON-FICTION

This was the Year of the Memoir for me and three very different memoirs stand out:

Provence, 1970 by Luke Barr (2013)

Food is one of the most vibrant reflections of culture, and when cultural trends shift, shed and shake, those who influence our taste buds must shift with it, or be pushed back to the dark corners of the kitchen cabinets with the jello molds and fondue pots. Provence, 1970 shows how some of our greatest food icons reconciled their beliefs in the superiority of all things French with the inevitable change in American tastes.

My Salinger Year by Joanna Rakoff (2014)

At its tender heart, My Salinger Year is a coming of age tale of a writer and an ode to being young and sort-of single in New York, living in an unheated apartment in Williamsburg and taking the subway to Madison Avenue to speak in plummy, tweedy tones with other underpaid literati. It is a gloriously, unabashedly nostalgic memoir and utterly charming.

The Chronology of Water by Lidia Yuknavitch (2011)

This isn't for everyone. Some will read and be exasperated or disgusted or disbelieving. I get that. I get that chaos and promiscuity and addiction are ugly and life is too short to waste reading about someone else's tragedy and self-destructive behavior. But something about this story—the goddamn gorgeous language, the raw power of its brutality—gave me so much comfort and solace. In Yuknavitch's word embrace, I felt the magic of self-acceptance and self-love, and the crazy-wonderful beauty of life.

FICTION

Americanah by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie (2013)

Race in America is an uncomfortable subject, mostly for white Americans. We still don't know where to look or what to do with our hands. We fidget and prevaricate. We, like blond-haired, blue-eyed, wealthy, liberal Kimberley in Americanah, use euphemisms like "beautiful" when we refer to black women so that everyone will know that not only are we not racist, but we think blacks are particularly worthy of our praise. Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie reflects our beliefs and behaviors back on us, illuminating our silliness and our masquerades, our ignorance and our misguided, but earnest attempts to understand the impossible: what it's like to be something other than white in this race-anxious society.

Life Drawing by Robin Black (2014)

Perfidy in marriage is a tried and true theme. Perhaps even time-worn. Oh, but not in Robin Black's hands. Her craft is brilliant. In a year when I have read some massive tomes (e.g. The Luminaries, Goldfinch, Americanah), Black's sheer economy of word and image is powerful and refreshing. Yet there is nothing spare in her syntax. Her sentences are gorgeous:

The day is thinning into darkness, the light evaporating, so the fat, green midsummer trees not fifty feet away seem to be receding, excusing themselves from the scene.

and

Bill and I had been tender with each other in the way only lovers with stolen time can sustain. Even in parting, gentle, gentle, gentle, like the tedious people who must unwrap every present slowly, leaving the paper entirely intact.

The Enchanted by Rene Denfeld (2014)

There are few writers who can wrest hope from the pit of horror with such eloquence. I think of Elie Wiesel and Primo Levi, who chronicled their Holocaust experiences, or Maya Angelou and Toni Morrison showing us the wretchedness of slavery and Jim Crow. These writers compel us to bear witness to humanity's darkest hours with beautiful language. With the same poignant but unsentimental style, Rene Denfeld applies a tender, humane voice to the hopelessness of prison and death row. She pries open our nightmares, releasing mystical creatures as symbols that help us understand our complex, real fears.

All The Light We Cannot See by Anthony Doerr (2014)

Anthony Doerr’s prose is lovely. It pirouettes with grace on the fine line between lush and lyrical, flirting with magical realism, but never leaving solid ground. The imagination it takes to bring a reader into the head of a blind child learning to navigate her world so that we see, feel, smell, and hear as she does is breathtaking. The ability to evoke empathy without tumbling into sentimentality is admirable. The weaving together of so many scientific and historical details so that the reader is spellbound instead of belabored is nothing short of brilliant.

Redeployment by Phil Klay (2014)

These are masterfully crafted stories of war. Phil Klay walks in the footsteps of Tim O’Brien, Ernest Hemingway, and Wilfred Owen before him, but with a vision all his own. What elevates these stories above voyeurism and shock value is his pitch perfect writing. Klay's ear for dialogue, his eye for detail—offering just enough poetry in his prose to seduce, but not to saturate—and the immediacy and emotion of his characters’ voices reveal the power this young writer wields with his pen.

The Other Language by Francesca Marciano (2014)

As a reader and writer for whom place is nearly as important as character, I was delighted to find that Marciano speaks my language. From her native Rome to a haute couture boutique in Venice, from an old bakery turned House Beautiful in Puglia, to post-colonial Kenya, a remote village in Greece, central India, or to New York City, Marciano shows us how place defines character, and how travel strips us of our inhibitions and sometimes, our conscience.

Cailleach: The Hag of Beara by Leanne O'Sullivan (2009)

This slim volume of sensuous poetry takes the supernatural myths behind the Hag's many lives and distills them to human form, presenting a woman in love, not with gods from the sea, but with a humble fisherman. O'Sullivan's images are full of longing of the body and mind, emotional resonance woven with sensual pleasures.

Nora Webster by Colm Tóibín (2014)

As readers, we often gravitate toward lives played out on a grander scale—adventures, dalliances, crimes, and misdemeanors far more colorful than our own. But reader, if you haven’t experienced the transcendent storytelling of Ireland’s Colm Tóibín, you may not know what it’s like to feel the earth tilt with the most subtle of emotional tremors.

History of the Rain by Niall Williams (2014)

This is a book to savor, slowly and delicately. It pokes gentle, meta, self-mocking fun at the conventions of novel structure. If you are a reader who expects tidy packages of chronological storytelling, plot points, and story arcs, give this a try. You might be surprised what beauty can be woven outside the confines of the Fiction 101 blogosphere. And read with a notebook by your side, because you'll want to make note of each volume Ruth references in her vast library—it's a primer on Western literature's greatest works of poetry and prose. Tissues would be good, too. I reckon you won't make it through this with dry eyes.

Eyrie by Tim Winton (2014)

Eyrie is a vertiginous wobble through lives disintegrated by the slow acid drip of despair and addiction, held together by the thinnest strands of determination, survival, and devotion. Winton, like Cormac McCarthy, Louise Erdrich, Colm Toibin, Edna O'Brien, is a writer-poet. His prose has such density and texture; it is sensual and viscous. Australian vernacular is particularly rich, to the point of cloying, and Winton uses it to demonstrate the sharp class divides in this country that we think of as a model of social egalitarianism.

My last full read of the year was Virginia Woolf's To the Lighthouse. I'm still haven't found the words to describe it, either as a book or as a reading experience, so I won't even try. I'll just keep reading.

Happy New Year to All!