Last year I wrote about The Chronology of Water by Lidia Yuknatvitch, a book that changed the way I thought about truth, about telling my truths as a writer, as a woman. As my friend Debbie says, “I would follow Lidia Yuknavitch anywhere.” This is not a frivolous statement, for if you have read her writing, you know following Lidia means walking naked into the fire. It also means, as I learned this weekend in a two-day workshop with eleven other raw and beautiful souls, walking into an immense, fierce, loving heart.

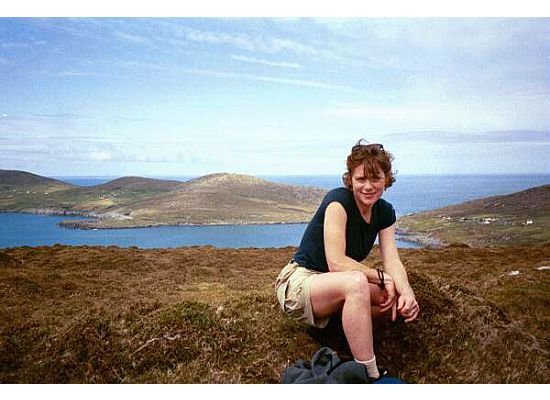

I’m nowhere near ready to write about this weekend’s workshop. What it revealed to me, where it will take me in my own writing—closer and closer to the truth, which is a very scary, necessary place to be—is too fragile. But I can say Lidia led me right back to the slipstream of desires and fears that I dove into earlier this summer in Ireland—a place of deep listening and turbulent silence.

I read Lidia’s most recent novel, The Small Backs of Children, several weeks ago and posted this reader response in Goodreads. I recreate it here to encourage you to explore Lidia’s writing, to hear her voice, to follow her anywhere. Prepare to be changed.

The Small Backs of Children by Lidia Yuknavitch

It is the little girl from Trang Bang, a village north of Saigon, running naked and screaming from pain and bombs and napalm. Her name is Kim Phuc.

It is the electrifying stare of an Afghan teen, her head wrapped in a blood-red scarf, her green eyes pulsing with anger and fear at the Soviet invasion that has decimated her home. Her name is Sharbat Gula.

It is the Sudanese child dying of starvation, stalked by a vulture. We don’t know the child’s name or what became of her. The photojournalist took his own life two months later.

These captured moments are real; they stand as records of war and poverty and our lack of humanity. They are images bound to the politics that created them. Do we call them art? These are girls whose bodies were used as canvases of emotion. Looking at them from our safe remove, we shake our heads and tut-tut. “So sad,” we say. “Someone should do something.” And then we turn away.

From these stories of children caught in the world of men, Lidia Yuknavitch adds an imaginary other: a girl airborne like an angel as her home and family are atomized behind her, in a village on the edge of a Lithuanian forest. Like the iconic images above, this photo travels around the world, garnering gasps and accolades. A copy of it hangs on the wall of a writer’s home—she is the photographer’s former lover—haunting the writer as she moves from one marriage to another, birthing a son, becoming pregnant with a daughter. The photographer wins a Pulitzer and moves on, to other conflicts, other subjects, other lovers. We learn, much later, that the girl’s name is Menas.

On the surface, the premise of The Small Backs of Children seems simple, the plot a means to distinguish this work as a novel rather than a prose-poem. The writer lay dying of grief in a hospital in Portland. She cannot climb out of the hole created by the birthdeath of her stillborn daughter. In an effort to save her soul, her friends determine the girl in the photograph—now a young woman, if she is still alive—must be found and brought to the States. Two lives saved. But this daughterless mother and motherless daughter do not meet until near the end. And the end could be one of many that Yuknavitch offers up, as if to say, “Does it matter? There is no end. Not even in death is there an end.”

What happens in between is a howl. A series of howls, ripped from the body in ecstasy and terror. The Small Backs of Children is an exploration of the body, the body as art, the body as politic, all the ways we use and lose control of our bodies, or have them used against us. Yuknavitch shocks again and again, until it seems these characters are holes into and out of which pour the fluids of sex and addiction, art and death. Nearly all but the writer, her filmmaker husband, and the girl (mirror-selves of the author, her husband and their ghost-daughter) seem driven by their basest desires, or become victims of their own obsessions. And although there is only one Performance Artist, they all seem to be playing at their artistic selves, conflating art and life.

The premise may be transparent, but the execution of the plot—the shifting of the narrative between voices, countries, and eras—becomes something political and murky, a metafiction loop of invented words, fragile sound bites, and acts of literary revolution.

Virginia Woolf is a palimpsest beneath the narrative. As in The Waves, The Small Backs of Children is told through several voices that loop and leap in quicksilver language. Yet unlike Woolf’s Bernard, Susan, Rhoda, Neville, Jinny, and Louis, we know Yuknavitch’s characters only by their artistic occupations: The Writer, The Filmmaker, The Poet, The Playwright, The Performance Artist, The Photographer, and, perhaps standing in for Percival, The Girl. This unnaming keeps us at a distance. But to read Yuknavitch is to know she honors experimental forms and shoves away convention.

Gustave Flaubert, arguably the creator of the modern novel, stated, “An author in his work must be like God in the universe: present everywhere and visible nowhere.” What would Flaubert make of Lidia Yuknavitch? For in The Small Backs of Children, the author is visible everywhere. In each word and image and scene, we inhabit her visceral presence. If you scooped up and ate her body-memoir The Chronology of Water, you will recognize not only the themes of child loss, savage sexuality, rape, addiction, the vulnerability of girls, the release and capture of water, you will recognize scenes and words and images. It is as if we are in a continuation of Yuknavitich’s story, swimming in her stream of consciousness.

She transcends the notion of the novel and enters something larger: the intersection of prose and poetry and memoir and reportage. And the reader spins around this crossroads, trying to make sense of it all. The language propelled me forward, even as I felt the story spinning me away. Like a work of visual art that is meant to provoke, that is devoid of answers, redemption, resolution—the photograph of a young girl in a moment of terror or loss say—The Small Backs of Children drained me until I was a shell without reason, reduced to a body quivering with animal emotion.