I dig distillation. I dig that a mad farmer-artist-scientist can take a bushel of rye, wheat, potatoes, corn, grapes, sugar cane--what have you--ferment it to potent alcohol and pass it through a still to create a liquid that will straighten the tangle of your intestines with searing, rich, and lusty fire. Without getting all spirit-ual on you, the purpose of distillation is to separate the impurities found in the heads and the tails--the first and last parts of the distillation process--from the heart--the desirable middle portion. Less heads and tails in the heart, the purer the spirit.

I'm a Cognac, Armagnac, Scotch whisky, and Bourbon girl, myself. I like my brouillis bold and my congeners cocky. Give me smoky peat and sour mash--I want booze with grit. Water-white, über-distilled, neutral vodka has never done much for me. Until now.

Oh, don't worry. I'm not pounding the Absolut in my pursuit of the writing life. Tazo Green Ginger tea is my potion of motion while huddled over the laptop. It's just that I've spent the past six weeks distilling The Novel with more effort than a custom-made Christian Carl pot still with multiple rectification columns.

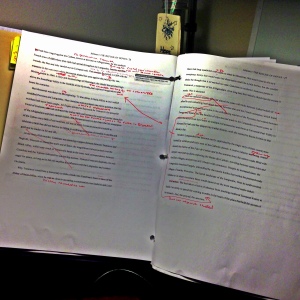

Since my foray into full-time writing began in mid-July, I've been editing. I started at the beginning of The Novel and I'm working my way, scene by scene, to the end. I'm filling in plot holes, finessing the details of setting and history, and adding dimension to my characters. Revising. Rewriting. Amending. Emending. Butchering. Compiling. Tightening. Refining. I nearly entitled this blog post "Revising is like Vodka" because it feels as though I haven't done much writing. But it's all writing, isn't it? It might not be the curl-up-on-the-sofa-at-4-am-with-Pilot-Fine-Point-and-Moleskine that got me the meat of a novel, but it's the work that will get me to the heart of all I've written.

Since my foray into full-time writing began in mid-July, I've been editing. I started at the beginning of The Novel and I'm working my way, scene by scene, to the end. I'm filling in plot holes, finessing the details of setting and history, and adding dimension to my characters. Revising. Rewriting. Amending. Emending. Butchering. Compiling. Tightening. Refining. I nearly entitled this blog post "Revising is like Vodka" because it feels as though I haven't done much writing. But it's all writing, isn't it? It might not be the curl-up-on-the-sofa-at-4-am-with-Pilot-Fine-Point-and-Moleskine that got me the meat of a novel, but it's the work that will get me to the heart of all I've written.

I entered a couple of "Opening Chapters" contests--these are where you send the first pages of your novel and hope you make it far enough in the process to have your work seen by an agent and/or an editor. It took me over two weeks of mind-numbing revision to prepare forty double-spaced Times New Roman 12-point pages. I changed a major plot point, rearranged a ton of scenes, and sheared off 6,000 words. SIX THOUSAND WORDS. Five percent of my work, gone. The Novel went on a crash diet. I distilled those opening pages over and over again until my inner refractive index said "Enough."

I sent off my entries and walked away from The Novel. A few days later I sat down to reread my forty pages of marvelously redacted prose.

AAIIGGHH!!!!

AAIIGGHH!!!!

Three pages in and I was running for the red pen. Heads and Tails all over the place. Does the distillation never end?

Author Ann Hood told a packed crowd at the Port Townsend Writers' Conference in early July that she had revised her novel The Knitting Circle thirty-five times. Thirty-five times BEFORE sending the manuscript to her editor, even before letting her first reader--her husband--have a peek. Thirty-five trips to Kinkos to pick up a boxed copy of the current draft.

Ann left us with a laundry list of outstanding editing practices, which I may share with you when I muster up the courage to face the list again. Each of her suggestions could be a full-draft edit exercise; since I wrote down twenty parts to the process, I reckon I've got at least twenty full edits ahead of me.

Distillation: the process by which aromas, flavors, and alcohol are concentrated and negative compounds removed.

I'll drink to that. But my title simile has its descriptive limitations. Let's not forget that impurity is another name for character. You can have your vodka martini. Pour me a Bunnahabhain 18 Year Old. Neat.